We don’t know where the Church is not?

Have you heard either of the following phrases being used in the church?

- “We know where the Church is but we cannot be sure where it is not”

- “We know where the Holy Spirit is, but we don’t know where He is not”

Neither of these sayings derive from the witness of the fathers and saints. They’re often used by Orthodox Christians who abide in them for a multitude of reasons:

- They don’t really know the tenets of Orthodoxy that well.

- Out of a misguided notion of love (that directly contradicts the witness of saints like St. Paisios the Athonite).

- They are terrified that the truth will offend others.

- They don’t particularly care for the dogma of the Orthodox Church.

Sometimes, people repeat this interesting statement. I’ve heard it many times over the years of my priesthood that “we know where the Church is, but we don’t know where the church isn’t”… have you ever heard that statement? It’s very common… and it’s hideously wrong.

— Fr. Josiah Trenham, Patristic Nectar, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dC-yEbodaio

In this light, we will attempt to examine these quotes closely. We will examine the original full quote in context, a brief portrait of Metropolitan Kallistos Ware and his ecumenical involvement (including the World Council of Churches), the witness of the saints and fathers regarding the Church and the Holy Spirit, the error of Branch Theory in relation to the Creed, misguided motivations for these phrases, and finally, we will examine the words of Alexey Khomiakov from whom this teaching is often said to ultimately derive, clarifying his actual stance.

II. Tracing the Popular Source: Metropolitan Kallistos Ware and His Ecumenical Context

A. Ware’s Formulation

It was largely Metropolitan Kallistos Ware (formerly Timothy Ware) who popularized the simplified ambiguous version as we know it today in the very popular book: The Orthodox Church: An Introduction to Eastern Christianity.

This book due to it’s popularity, has promoted a sentiment that exists largely in the English-speaking world, promoting a moderate view emphasizing invisible bonds and an invisible church that risks diluting the clear Patristic understanding of the Church’s unique identity. The full quote is as follows:

If Orthodox claim to constitute the one true Church, what then do they consider to be the status of those Christians who do not belong to their communion?

Different Orthodox would answer in different ways, for although nearly all Orthodox are agreed in their fundamental teaching concerning the Church, they do not entirely agree concerning the practical consequences which follow from this teaching. There is first a more moderate group, which includes most of those Orthodox who have had close personal contact with other Christians. This group holds that, while it is true to say that Orthodoxy is the Church, it is false to conclude from this that those who are not Orthodox cannot possibly belong to the Church. Many people may be members of the Church who are not visibly so; invisible bonds may exist despite an outward separation. The Spirit of God blows where it chooses and, as Irenaeus said, where the Spirit is, there is the Church. We know where the Church is but we cannot be sure where it is not.

This means, as Khomiakov insists, that we must refrain from passing judgement on non-Orthodox Christians:

‘Inasmuch as the earthly and visible Church is not the fullness and completeness of the whole Church which the Lord appointed to appear at the final judgement of all creation, she acts and knows only within her own limits … She does not judge the rest of humankind, and only looks upon those as excluded, that is to say, not belonging to her, who exclude themselves. The rest of humankind, whether alien from the Church, or united to her by ties which God has not willed to reveal to her, she leaves to the judgement of the great day.’

— Metropolitan Kallistos Ware, The Orthodox Church, Chapter 16: The Orthodox Church and the Reunion of Christians.

There are more than a few problems with this interpretation, as we will soon elaborate on.

B. A Portrait of Metropolitan Kallistos Ware

Metropolitan Kallistos Ware (who is now reposed) was and remains one of the most popular voices in Orthodoxy. In many Orthodox churches, his books and writings are inexplicably promoted higher than the writings and witness of our Orthodox fathers and saints.

Unfortunately, he often maintained stances that were very different from the fathers. He:

- Was deeply involved in ecumenism, which is vehemently spoken against by the fathers and saints.

- Participated in ecumenical meetings with Anglican, Roman Catholic, and Pentecostal Churches.

- Closely embraced and gave the kiss of peace to Pope Francis, who is recognized by the church as a heretic.

- Was actively involved with and lauded by the World Council of Churches (WCC).

- Supported the revival of deaconesses and questioned the exclusively male priesthood as merely ‘tradition’.

- Showed openness to evolution/panentheism, challenging traditional Patristic views on Creation.

- Sympathetically explored universalism (apokatastasis), again in direct contradiction with the consensus witness of the saints and fathers.

- Supported receiving the heterodox via Chrismation, blurring essential Church boundaries.

- Reframed historical schism, obscuring the nature of heresy and implying shared Orthodox culpability for divisions.

- Was received into the church through chrismation, which is also not the appropriate way for Heterodox to be received into the church.

He can be seen here giving the kiss of peace to the Pope of Rome. This is categorically unacceptable, given the nature and prerequisites of this sacred act.

Is it permissible for us to use the kiss of peace — the ultimate moment of manifesting unity in truth and love—differently than what has been proscribed by our liturgical tradition? That is, by downgrading it to a gesture of social politeness and socialization, on the level of emotion or of ecclesiastical politics? […] Is the liturgical kiss an independent act, or is it the prerequisite so that “with one mind we may confess” the Trinitarian Dogma, Theology, as this was set out in the Creed? When there is no common confession of faith (since there is not common theology) what purpose does a kiss of peace between an Orthodox hierarch and a heretical leader serve?

— Protopresbyter Anastasios K. Gotsopoulos, On Common Prayer with the Heterodox

C. The World Council of Churches (WCC) Connection & Critique

That Metropolitan Kallistos Ware was actively involved with, and was highly lauded by the W.C.C is no small matter for those who care what our saints and elders have to say to us:

When even the champion of the World Council of Churches, Metropolitan Meliton of Chalkedon, is forced to admit: “It is an undoubted fact that the W.C.C. is 99% under the control of Protestantism and strongly carries its mark,” what more evidence do we Orthodox need to sever relations with them before we crush any hope left in them that the truth really exisis unique, intact and lucid to be found in the One, Holy, Orthodox Church of Christ?

— Geronda Ephraim of Arizona, A Call from the Holy Mountain, pg. 44

in the 1970s however, as Father Seraphim Rose recorded at the time, the Soviet State sought to force the Russian Orthodox Church into active membership of the W.C.C. in order to destroy its uniqueness in the minds of the Russian people.

— Fr. Spyridon Bailey, Orthodoxy and the Kingdom of Satan

And today, more than ever, the dogmatic conscience of the plēroma of the Church is in danger of being altered by the ecclesiology being cultivated by the WCC.

— Committee of the Holy Community of Mount Athos on Dogmatics, Memorandum, from On Common Prayer with the Heterodox

One of the tools used by Ecumenism in order to achieve its aims is Syncretism, that deadly foe of the Christian faith, which is promoted by the so-called “World Council of Churches,” or rather “World Council of Heresies,” as it has rightly been characterized.

— Metropolitan Seraphim of Piraeus, A Letter to Pope Francis

At what other time have Orthodox and heretics collaborated for the organization of “interconfessional prayer”, as has occurred within the WCC?

— Protopresbyter Anastasios K. Gotsopoulos, On Common Prayer with the Heterodox

This pan-heretical alchemy is being inspired through the so-called World Council of Churches. We think that the term is not true to the fact, for it does not concern a World Council of Churches but a World Council of Will Worship. The only god to demand a tribute of worship there will be the fallen Beelzebub who through his representative amongst men, the Antichrist, will try to substitute his own will for the faith and worship of the true God. For in Ecumenism there is no personal God; for consistent ecumenists the doctrine of the Trinitarian God is utterly rejectable.

— Geronda Ephraim of Arizona, A Call from the Holy Mountain, pg. 42

The establishment of The World Council of Churches was financially supported by the Rockefeller Foundation which first appointed John Foster Dulles to lead the National Council of Churches in America. Dulles was a member of the Council On Foreign Relations and also chairman of the Rockefeller Foundation Trustees. Dulles was sent to the founding conference of the W.C.C. in Amsterdam in1948 to promote the Rockefeller strategy. It had been recognised that not only Orthodox, but also Roman Catholic and Evangelical Christians were opposed to the idea of doctrine being treated as secondary to the idea of outward unity at any cost. And so the Rockefeller plan was to establish a new idea that would speak over theological differences; this was what became known as the “social gospel” . By encouraging Christians to focus primarily on collaboration to help others, it was understood that they would quickly form social and organisational bonds that would become stronger than the content of the faith they professed. Christians were taught to focus on social justice as the primary aim of their response to God, which enabled the replacement of traditional Christian spirituality with a worldly, materialistic version of Christianity. Serving our neighbour has always been a fundamental Christian concept, but now it was to be the main purpose of Christianity. In this way, any objection raised about doctrinal differences could be portrayed as disruptive and creating disunity which threatens the social action of the ecumenists.

— Fr. Spyridon Bailey, Orthodoxy and the Kingdom of Satan, Chapter 7: Ecumenism

The main coordinator of the 1993 Re-imagining conference, Mary Ann Lundy, is now the Deputy Director of the World Council of Churches. At the 1998 Re-imagining conference, she made clear the agenda of both feminist theology and modern-day ecumenism: “We are learning that to be ecumenical is to move beyond the boundaries of Christianity. You see, yesterday’s heresies are becoming tomorrow’s Book of Order.” This statement from a WCC Deputy Director starkly illustrates the council’s trajectory towards doctrinal relativism and the embrace of ideologies fundamentally alien to Orthodox Tradition, as figures like Fr. Seraphim Rose warned.

— Hieromonk Damascene, Orthodoxy and the Religion of the Future, Epilogue

In 1993 the first “Re-imagining” conference was held in Minneapolis, Minnesota, in conjunction with the World Council of Churches’ Ecumenical Decade of Churches in Solidarity with Women. The conference was attended by over two thousand participants from twenty-seven countries and fifteen mainline denominations, most prominently the Presbyterian, Methodist, Lutheran, Roman Catholic, United Church of Christ and American Baptist. One third of the participants were clergy. Speaking of the need to “destroy the patriarchal idolatry of Christianity,” the conference speakers rejected and at times ridiculed the Christian dogmas of the Holy Trinity, the Fall of man, the unique incarnation of God in Jesus Christ, and the redemption of man by Christ’s death on the Cross. In place of these articles of faith, the conference promoted pantheism, shamanism, and homosexual rights. The participants took part in a “liturgy” wherein milk and honey were used rather than bread and wine, and the goddess “Sophia” was worshipped rather than Jesus Christ. The chant was repeated: “Our Maker Sophia, we are women in your image … with our warm body fluids we remind the world of its pleasure and sensations.” At a later Re-imagining conference held in 1998, Sophia-worshipping participants also shared biting into large red apples to express their solidarity with Eve, whom they regard as a heroine for having partaken of the forbidden fruit.

— Fr. Seraphim Rose, Orthodoxy and the Religion of the Future

In our first Sorrowful Epistle, we wrote in detail on how incompatible with our Ecclesiology was the participation of Orthodox in the World Council of Churches, and presented precisely the nature of the violation against Orthodoxy committed in the participation of our Churches in that council. We demonstrated that the basic principles of that council are incompatible with the Orthodox doctrine of the Church. We, therefore, protested against the acceptance of that resolution at the Geneva Pan-Orthodox Conference whereby the Orthodox Church was proclaimed an organic member of the World Council of Churches. Alas! These last few years are richly laden with evidence that, in their dialogues with the heterodox, some Orthodox representatives have adopted a purely Protestant ecclesiology which brings in its wake a Protestant approach to questions of the life of the Church, and from which springs forth the now popular modernism.

— Metropolitan Philaret of New York, Zealous Confessor for the Faith

III. The Unwavering Patristic Witness: Christ is Here, and Not Elsewhere

In direct contrast to the ambiguity introduced, the traditional Orthodox teaching is clear. St. Theophan the Recluse provides a definitive statement:

If any man shall say to you, Lo, here is Christ; or, lo, He is there; believe him not (Mark 13:21).” Christ the Lord, our Savior, having established upon earth the Holy Church, is well pleased to abide in it as its Head, Enlivener, and Ruler. Christ is here, in our Orthodox Church, and He is not in any other church. Do not search for Him elsewhere, for you will not find Him. Therefore, if someone from a non-Orthodox assemblage comes to you and begins to suggest that they have Christ — do not believe it. If someone says to you, “We have an apostolic community, and we have Christ,” do not believe them. The Church founded by the Apostles abides on the earth — it is the Orthodox Church, and Christ is in it. A community established only yesterday cannot be apostolic, and Christ is not in it. If you hear someone saying, “Christ is speaking in me,” while he shuns the [Orthodox] Church, does not want to know its pastors, and is not sanctified by the Sacraments, do not believe him. Christ is not in him; rather another spirit is in him, one that appropriates the name of Christ in order to divert people from Christ the Lord and from His Holy Church. Neither believe anyone who suggests to you even some small thing alien to the [Orthodox] Church. Recognize all such people to be instruments of seducing spirits and lying preachers of falsehoods.

— St. Theophan the Recluse, Thoughts for Each Day of the Year, pg. 40 (The Tuesday following the Sunday of the Publican and Pharisee)

St. Theophan the Recluse contradicts the interpretation of Metropolitan Kallistos Ware in 4 broad ways:

- Presence of Christ: Metropolitan Kallistos allows for the possibility of the Holy Spirit and thus the Church existing beyond the visible Orthodox communion (“cannot be sure where it is not”). St. Theophan the Recluse flatly denies this possibility, stating Christ “is not in any other church.”

- Nature of Non-Orthodox Christians: Metropolitan Kallistos perspective allows for nuance, suggesting non-Orthodox individuals might have “invisible bonds” to the Church and should not be judged harshly. St. Theophan the Recluse views non-Orthodox groups as definitively lacking Christ and warns believers not to believe their claims, portraying them as potentially misleading.

- Certainty vs Mystery: Metropolitan Kallistos Ware emphasizes the limits of human knowledge (“ties which God has not willed to reveal”) and the mystery of God’s action. St. Theophan the Recluse expresses absolute certainty about the boundaries of Christ’s presence, leaving no room for such mystery regarding other Christian bodies.

- Moderate: The Metropolitan says that there are 2 groups in Orthodoxy, and that the more moderate group does not consider those outside of Orthodoxy, not of the church. This implies that St. Theophan the Recluse, and many of our saints who shared the exact same stance were somehow immoderate. St. Theophan the Recluse, who undoubtedly has more authority being a canonized saint of the church, and who is recognized by other saints and elders in the church, makes absolutely no such distinction.

In essence:

- The Metropolitan presents a view that holds onto Orthodox claims while maintaining a degree of openness and humility about the ultimate status of those outside.

- St. Theophan the Recluse presents a much stricter, more definitive, and exclusive view, asserting that salvation and the presence of Christ are found only within the visible Orthodox Church and warning strongly against any suggestion otherwise.

We recognize the contributions of Metropolitan Kallistos Ware to the English speaking world, however, we must recognize the greater authority of the saints, of which St. Theophan the Recluse speaks from, giving us the consensus of the saints on this topic.

IV. Unmasking the Underlying Error: Branch Theory vs. The Creed

A. What is Branch Theory?

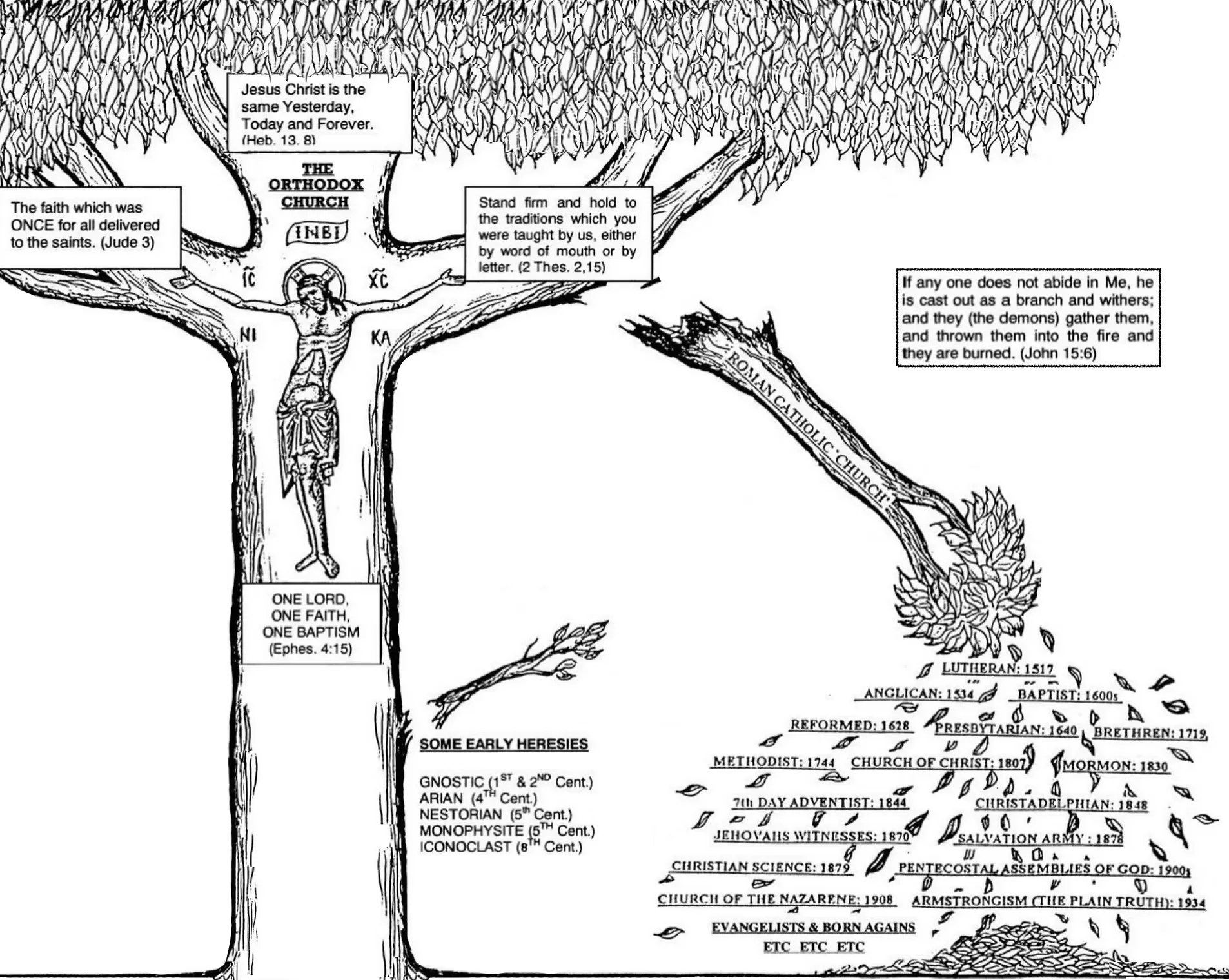

The ambiguous phrase “We know where the Church is but we cannot be sure where it is not” often finds its underpinning in an ecclesiological error known as Branch Theory.

Branch theory is the belief seeks to state that other denominations, while not visibly united with the Orthodox Church, are a part of the same one branch, but are invisibly united.

Branch theory of course, is considered a heresy. Even the OCA outright rejects this notion:

To say that “it’s all the same, there’s only one Christ, there’s a variety of different ways to express our belief in Him,” is to flatly ignore the history of Christianity, specifically the first two Ecumenical Councils, which discerned once and for all the truth concerning the person and mission, the humanity and divinity, of Jesus Christ—and which, incidentally, in no way subscribes to the branch theory.

— https://www.oca.org/questions/history/orthodox-christianity-and-the-branch-theory

Branch Theory is circumventing of the abundantly clear doctrine stated in The Creed. It has no basis in Orthodoxy, and even originates from a Catholic Theologian, Cardinal Newman:

Ecumenism began with Cardinal Newman’s branch theory.

— Hieromartyr Daniel Sysoev, Questions to Priest Daniel Sysoev

Branch Theory is an unfortunately a commonly held belief of Anglicans, of which the Metropolitan both converted from, and dialogued with for the majority of his life.

"For his outstanding contribution to Anglican-Orthodox theological dialogue,” Metropolitan Kallistos was awarded the Lambeth Cross for Ecumenism by the Archbishop of Canterbury.

— World Council of Churches, https://oikoumene.org/news/a-tribute-to-metropolitan-kallistos-ware-of-diokleia

While not wishing to condemn or judge, we apprehensively wish to warn people about the Metropolitan Kallistos Ware’s Anglican background (and efforts in dialog), so that they may be protected against adopting a phronema that is not Orthodox.

The idea that “we cannot be sure where the church is not”, is an identical sentiment to the idea that there is an invisible church. Therefore, this is nothing more than a manifestation of branch theory, as it expresses a unity in faith that can’t be outwardly seen.

We acknowledge Orthodoxy as the one true church that meets all the criteria of being this church. By definition, there cannot be another.

If there can be another, then the only means by which to validate those outside the Orthodox faith, is branch theory, this invisible church, that being invisible, we supposedly cannot be sure where it is not.

Therefore, the statement “We know where the Church is but we cannot be sure where it is not” is either a refutation of the Creed, or an indirect manifestation of branch theory.

B. The Uncompromising Creed: One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic

In the Creed, the bedrock of our Faith, we confess our belief “in One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church.” These four marks are not mere suggestions; they are the divinely revealed identifiers of Christ’s Body. They tell us what and where the Church is, and therefore, necessarily, where She is not. We know that we uniquely have maintained the apostolic, universal tradition. We are one.

There are no other truly Christian churches outside of Orthodoxy, as St. Theophan the Recluse has said (and many of our saints and fathers this).

The Orthodox Church boldly proclaims herself this singular Church, repeatedly. To say “we cannot be sure where the church is not” is to implicitly call the Ecumenical Councils, the Saints, and the Elders liars and fools. It’s an embrace of relativism, suggesting the Church might just vaguely exist “out there” in communities lacking the defining marks confessed in the Creed – communities about which the Apostle John warned, “They went out from us, but they were not of us…” (1 John 2:19).

Anyone who disagrees with this, simply disagrees with The Creed or desires to circumvent it in a way that no saint ever directly avowed:

- St. Philaret of Moscow: His Catechism defined the Church by “Orthodox faith, the law of God, the hierarchy, and the Sacraments” and stated salvation is obtained only within Her, the sole Ark. These elements define the One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic reality.

- Saint Cleopa of Romania: Explained the Church is called “Catholic” in the Creed because She possesses the entire, undistorted truth given by Christ (unlike Heterodoxy), and “Apostolic” because She maintains the Apostles’ doctrine unadulterated through unbroken succession (also unlike Heterodoxy).

- St. Hilarion Troitsky: Declared that communities separated by heresy or schism (which the Heterodox are by definition) cease to be the Church. Separation violates the Oneness and Catholicity (fullness of truth) confessed in the Creed.

V. Misguided Motivations: The Perversion of “Love” and Fear of Truth

A. False Love vs. True Orthodoxy

Atheists, pagans, and even Heterodox all claim to love and to know love. We as Orthodox therefore are not in the least unique in this external, outward expression of love.

But yet, we know that love is only possible in the Orthodox Church. And so, knowing that the keyword love alone cannot advocate for Orthodoxy, how is Orthodoxy differentiated from all other faiths and religions, beliefs and non-beliefs?

Orthodoxy (from Ancient Greek ὀρθοδοξία (orthodoxía) ‘righteous/correct opinion’) is adherence to a purported “correct” or otherwise mainstream - or classically-accepted creed…

Ortho means “correct”, and doxy means “way”. Orthodoxy is the correct way, or right belief. This is what makes us Orthodox. It’s right in the name. Does it say Agapedoxy? Forgive me, it does not.

When we come to Orthodoxy, we uniquely affirm the correct doctrine and dogma of the church above all else, and all else flows from this. The love that we avow, MUST stem from this truth and correctness.

Love, my dear brethren, is omnipotent, as mighty as death, but its strength always goes hand in hand with truth.

— Geronda Ephraim of Arizona, A Call from the Holy Mountain, pg. 45

And so, what does it mean when we proudly elevate ourselves about the saints of the church as somehow beacons of love, whilst willing to throw away the dogma of the church? In that moment, we in practice become Heterodox and atheists. They too, elevate their own idea of love, above the teachings of the church. And so we are not in the least different from them when we behave in this manner.

B. The Fear of Offending vs. Speaking Truth

In our times, many Orthodox Christians are terrified of offending those outside the Ark of Salvation. This fear often leads to an embrace of ambiguity that conflicts with the clear witness of our Saints. Convenient, conscience-soothing slogans, detached from the whole of Patristically-grounded thought, are used to justify a position that sidesteps difficult truths.

Unfortunately, these days everyone tries to make a showcase how good they are because they have allowed the European spirit of politeness and courtesy to become a priority. Wanting to show how superior their courtesy is, they end up bowing to the two-homed devil.

— St. Paisios the Athonite, With Pain and Love for Contemporary Man, pg. 385

These slogans can become tools to chip away at the rock-solid Orthodox understanding of the Church, replacing Patristic certainty with modern sentimentality. As St. Paul warned, “the time will come when they will not endure sound doctrine, but according to their own desires, because they have itching ears, they will heap up for themselves teachers; and they will turn their ears away from the truth, and be turned aside to fables” (2 Timothy 4:3-4). The desire to avoid offending can, in this way, lead to a dilution of Orthodox truth for the sake of worldly acceptance or ecumenical expediency, a point that will be further illustrated when discussing misinterpretations of Aleksey Khomyakov.

There’s no need for us to tell Christians [Heterodox] who aren’t Orthodox that they’re going to hell or that they’re antichrists; but we also mustn’t tell them that they’ll be saved, because that’s giving them false reassurances, and we’ll be judged for it. We have to give them a good kind of uneasiness — we have to tell them that they’re in error.

— St. Paisios the Athonite, Saint Paisios of Mount Athos, pg. 658

VI. The Holy Spirit: Within the Ark, Calling to the Ark

A. Deconstructing “We cannot be sure where the Holy Spirit is not"”

The alternative phrase concerning the Holy Spirit: “We know where the Holy Spirit is, but we don’t know where He is not” has been offered specifically as a correction to the other problematic “We don’t know where the church is not” phrase", which aims for greater precision by distinguishing the defined Church from the Spirit’s mysterious actions.

(note: while Fr. Josiah Trenham seemingly popularized this saying, he is unfortunately being misquoted by many people, because he did actually say this in a much much more precise way).

However, this too, is not completely accurate:

However, that does not mean that the Spirit of God was not in the world at all, but His presence was not so apparent as in Adam or in us Orthodox Christians.

— St. Seraphim of Sarov, On the Acquisition of the Holy Spirit, Conversation with Motovilov

As witnessed by St. Seraphim of Sarov’s explanation above, our saints cared about the preciseness of their theological explanations. We too, must strive for this preciseness, not allowing ourselves to abide in laziness that lacks such precision.

There is also an undoubted hierarchy being expressed here by St. Seraphim of Sarov, which is very unlike the “we don’t know where the Holy Spirit is not” quote.

“We don’t know where the Holy Spirit is not statement” is not an pronouncement of St. Athanasius, St. Basil, St. John Chrysostom, or any saint or any Ecumenical Council. They are the fruit of more modern theological discussions, and in their popular, sloganized forms, they stand to dilute the boundaries of the church. Compare this to the unwavering clarity of St. Seraphim of Sarov, St. Theophan the Recluse, and all the saints referenced in this text.

Also, is it not splitting theological hairs to say “well we know where the church is, but we don’t know where the Holy Spirit is”? Can acquisition of the Holy Spirit really be divorced from the Church? Is it not it clear that these fly-by statements lead to potentially disastrous theological conclusions?

Our saints and fathers had ZERO difficulty agreeing on dogma, but had much difficulty on the formulation. This meant that they spent much effort to formulate dogma to not be interpreted in a heretical manner:

In the years when the dogmas were being formulated, the Fathers’ experience was identical. So when the Fathers spoke from their own experience, they could easily reach agreement on putting it into words. It was easy. There was no difficulty. Where did the difficulty lie? It was not formulating the dogma that was difficult, but formulating it in such a way that it could not be interpreted in a heretical manner. That was the Fathers’ problem.

— Fr. John Romanides, Empirical Dogmatics, pg. 102

It is without doubt that many of our more ecumenistically minded Orthodox Christians subscribe to such things as branch theory. These Orthodox Christians relish in these quotes, and use them often. In many progressive jurisdictions, these “we don’t know where the church / Holy Spirit is not” quote are often the first thing inquirers and catechumens are drilled on, and even memorize.

We are responsible for leading others astray, and as such, we are responsible for the preciseness of our formulation of dogma. We should make great attempts to be very precise as to not encourage ecumenists and heretics. Do we not wish to follow the fathers and saints by spending great efforts as to not formulate something carelessly? Will God not call us accountable for our carelessness, especially if leads people to an conclusion that is not Orthodox?

Let us say finally: much of the goal with these aforementioned quotes is not theological precision, but avoiding the unpleasantness of telling the truth to the Heterodox. As Saint Paisios says, we must tell them they are “in error”. It is very true that we as Orthodox Christians often fear putting down Heterodox more than we fear betraying Orthodoxy and speaking truthfully.

As St. Gregory the Theologian warned, “An evil peace is more grievous than a pious war.”

B. Patristic Witness on the Spirit & Sacramental Necessity

Fr. Seraphim Rose addresses these claims of the gifts of Holy Spirit being outside the one, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic church:

And yet it is precisely the Church, and nothing else, that our Lord Jesus Christ established as the means of communicating grace to men. Are we to believe that the Church is now to be superseded by some ‘new revelation’ capable of transmitting grace outside the Church, among any group of people who may happen to believe in Christ but who have no knowledge or experience of the Mysteries (Sacraments) which Christ instituted and no contact with the Apostles and their successors whom He appointed to administer the Mysteries? No: it is as certain today as it was in the first century that the gifts of the Holy Spirit are not revealed in those outside the Church.

— Fr. Seraphim Rose, Orthodoxy and the Religion of the Future

To suggest that the Holy Spirit imparts salvific grace or sustains spiritual life within heterodox or schismatic communities, in a manner equivalent to His indwelling in the Orthodox Church, is a profound theological distortion, as already explained:

However, that does not mean that the Spirit of God was not in the world at all, but His presence was not so apparent as in Adam or in us Orthodox Christians.

— St. Seraphim of Sarov, On the Acquisition of the Holy Spirit, Conversation with Motovilov

Such a view inevitably diminishes the absolute necessity of the Church’s God-given Mysteries (Sacraments) – Baptism, Chrismation, the Holy Eucharist, Confession, Holy Unction, Marriage – which, according to the Fathers like St. Theophan the Recluse (as highlighted by Fr. Seraphim Rose), are the ordained means through which the Holy Spirit descends to incorporate believers into Christ’s Body and grant the grace leading towards salvation. As Fr. Seraphim Rose conveys the unwavering Patristic witness, particularly citing St. Theophan the Recluse:

“The great Orthodox Father of the 19th century, Bishop Theophan the Recluse, writes that the gift of the Holy Spirit is given ‘precisely through the Sacrament of Chrismation, which was introduced by the Apostles in place of the laying on of hands’… ‘We all—who have been baptized and chrismated—have the gift of the Holy Spirit … even though it is not active in everyone.’ The Orthodox Church provides the means for making this gift active, and ‘there is no other path… Without the Sacrament of Chrismation, just as earlier without the laying on of hands of the Apostles, the Holy Spirit has never descended and never will descend.’”

— Fr. Seraphim Rose, Orthodoxy and the Religion of the Future (quoting St. Theophan the Recluse)

This affirms that the normative impartation of the Holy Spirit for incorporation into Christ and salvation occurs through the Church’s Sacraments. There is no other revealed path. To imply otherwise renders these indispensable means optional and the Church Herself ultimately unnecessary.

C. The Spirit’s True Purpose Outside the Church

A dangerous ambiguity often arises when discussing the Holy Spirit’s work beyond the visible boundaries of the Orthodox Church. While Orthodoxy affirms God’s universal desire that “all men to be saved and to come to the knowledge of the truth” (1 Timothy 2:4) and the Spirit’s capacity to act providentially in the world, to “convict the world concerning sin and righteousness and judgment” (John 16:8), it is a grave error – often born of misplaced sentimentality or ecumenical pressure – to misinterpret the purpose and limits of this external operation. We must adhere strictly to the Patristic understanding.

To acknowledge the Spirit’s activity outside the Church is not, in any sense, to validate the separated bodies or condone the errors they maintain. Such thinking fundamentally misunderstands the Orthodox teaching. The witness of the Saints and Fathers is consistent and clear: any authentic movement of the Holy Spirit upon those outside the Church serves ultimately as a summons towards the fullness of Truth residing uniquely within the One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church. It is a preparatory grace, intended to lead wanderers towards the fulfillment of Christ’s explicit words: “And other sheep I have which are not of this fold; them also I must bring, and they will hear My voice; and there will be one flock and one shepherd” (John 10:16). This divine pronouncement points not to a nebulous collection of disparate groups legitimized by a vague notion of spiritual presence, but to a singular, unified flock under the one true Shepherd.

Therefore, the assertion that sufficient grace for salvation exists outside the canonical Orthodox Church contradicts the explicit testimony of the Fathers and the Church’s unwavering self-understanding. True Christian love compels the clear proclamation of this truth, however challenging it may seem. The Holy Spirit’s work outside the Church must be understood as a call towards the Ark, the Spiritual Hospital (as St. John Chrysostom termed the Church), the Orthodox Church – the sole repository where the fullness of grace and the divinely established means of salvation are found. Christ Himself declared, “I am the way, the truth, and the life. No one comes to the Father except through Me” (John 14:6), and His Body, the Church, is the extension of that Way, Truth, and Life in this world. There is definitively “one Lord, one faith, one baptism” (Ephesians 4:5), not many paths validated by the Spirit.

Any interpretation that twists the Spirit’s external work into a validation of heresy, a blessing upon schism, or evidence for alternative paths to salvation fundamentally corrupts the Gospel message. It attempts to legitimize separation from the Body of Christ and effectively preaches “another gospel,” which St. Paul commands us to reject utterly: “But even if we or an angel from heaven should preach to you a gospel contrary to the one we preached to you, let him be accursed” (Galatians 1:8). This stands in direct opposition to the Church established by Christ as the “pillar and ground of the truth” (1 Timothy 3:15), wherein alone is faithfully proclaimed the Name of Jesus Christ, for “there is no other name under heaven given among men by which we must be saved” (Acts 4:12). The Spirit calls souls home to Orthodoxy; He does not establish rival households.

VII. Reclaiming Khomyakov: Rescuing a Father from Modern Distortion

A. Khomyakov’s Actual Orthodox Ecclesiology

Much of the popular understanding of Orthodox ecclesiology in the English-speaking world, particularly concerning the Church’s boundaries and relation to the heterodox, bears the strong imprint of Metropolitan Kallistos Ware. Ware himself leans heavily on the 19th-century lay theologian Aleksey Khomyakov for pivotal concepts. But this reliance demands critical examination: Does Ware’s influential interpretation faithfully represent the staunchly traditional and Patristically-grounded thought of Khomyakov, or has Khomyakov been selectively employed to underwrite a modern ambiguity he himself would have rejected?

Aleksey Khomyakov—a theologian of profound Orthodox piety and deep Patristic learning—has ironically become a source cited to justify the very ecclesiological ambiguity he would have abhorred. His words are often twisted to suggest the Church’s boundaries are fundamentally unknowable, a gross distortion of his staunchly Orthodox stance. Let this be unequivocal: Khomyakov’s entire theological corpus affirms the Orthodox Church as a singular, visible, and uniquely salvific body. His writings stand as a powerful witness against the relativism attributed to him.

Evidence for Khomyakov’s unwavering Orthodoxy is abundant, as documented by scholars like Archimandrite Luke (Murianka) in the work Aleksei Khomiakov: A Study of the Interplay of Piety and Theology¹:

- Foundation in Faith: His Orthodox faith was foundational to all his views (Bishop Gregory Grabbe, cited Murianka, p. 21).

- The Church is One: His ecclesiology clearly articulated the Church’s “essential nature… as a singular, united, organic, distinguishable body, wherein alone is to be found salvation” (Murianka, p. 25)—directly contradicting notions of an indefinable Church.

- Patristic Grounding: His thought was “thoroughly grounded in patristic sources,” remaining true “precisely to the basic and most ancient tradition of the Church Fathers” (Fr. Georges Florovsky, cited Murianka, p. 31).

- Sobornost’ and Truth: His concept of sobornost’ denoted unity in Truth, rooted firmly in the Orthodox Church as the focal point (Murianka, p. 22), not some vague inter-denominational accord.

- Unwavering Fidelity: He was consistently pious, Orthodox, and never betrayed this ecclesial consciousness (Nicolas Berdiev, cited Murianka, p. 29).

Therefore, using Khomyakov to buttress a diluted, ambiguous ecclesiology requires ripping his words from their context and ignoring his life’s witness. His actual concern was the Church’s refusal to usurp God’s judgment over individuals outside—never an ontological uncertainty about the Church’s own unique and defined nature. The real Khomyakov decisively refutes the modern fog his name is misused to create.

B. Metropolitan Ware’s Interpretation: An Ecumenical Re-Framing?

This misuse finds a prominent conduit in Metropolitan Kallistos Ware’s highly influential work, The Orthodox Church. While frequently citing Khomyakov, Ware’s presentation often subtly re-frames the theologian’s words through an ecumenical lens, contradicting the staunch defense of Orthodoxy’s distinct identity inherent in Khomyakov’s own work (as established above from Murianka’s study). Let’s examine two key instances:

1. On Not Judging Non-Orthodox & “Ties Not Revealed”: Ware quotes Khomyakov regarding the Church not judging outsiders and leaving them to the “great day,” highlighting the phrase “united to her by ties which God has not willed to reveal to her.” Ware frames this as Khomyakov insisting “we must refrain from passing judgement.”

- The Ecumenical Angle: This phrase (“unrevealed ties”) is easily seized upon to imply hidden, salvific connections between Orthodoxy and other bodies, thus blurring the Church’s defined boundaries and supporting the “we cannot be sure where the church is not” ambiguity.

- The Khomyakov Contrast: This interpretation ignores Khomyakov’s core ecclesiology. His point was about acknowledging God’s mysterious providence towards individuals without compromising the Church’s self-understanding as the sole Ark of Salvation (Murianka, p. 25). It was humility before God’s judgment, not ontological ambiguity about the Church Herself.

2. The Parable of the Three Disciples: Ware presents Khomyakov’s parable where the master tells the eldest (Orthodox) brother to thank the younger (heterodox) brothers, for “without them you would not have understood the truth which I entrusted to you.” Ware offers this as depicting “the Orthodox attitude to other Christians.”

- The Ecumenical Angle: This strongly implies mutual enrichment and validation of traditions that deviated (“added to” or “took away from” the truth). The master’s lack of anger further softens distinctions, promoting a relativistic view where denominations hold partial truths needed for a “fuller” understanding.

- The Khomyakov Contrast: Such an interpretation clashes violently with Khomyakov’s view of the Orthodox Church as the singular “focal point” for unity “under the banner of truth” (Murianka, p. 22), and his sharp polemics against Roman Catholicism and Protestantism. The idea that Orthodoxy needs heterodoxy to understand its own fullness of Truth is alien to Khomyakov. His parable, in context, more likely speaks to God’s providence in allowing truth to be preserved despite error, and perhaps how encountering error clarifies truth for the faithful—not an endorsement of the error itself.

In summary: while Khomyakov spoke with nuance on God’s judgment and unrevealed ways, Ware’s presentation uses these points selectively to bolster an ecumenical vision. This fosters an ambiguity that undermines clear Orthodox ecclesiology — an ambiguity Khomyakov himself, grounded firmly in the Fathers and the Creed, did not endorse but actively refuted.

VIII. Conclusion: A Call for Uncompromising Clarity

In essence, these popular yet un-patristic slogans are more than mere words; they are corrosive agents that eat away at the firm foundation of Orthodox ecclesiology. They stem from a misplaced “kindness” that prioritizes worldly comfort over eternal truth (often born from misinterpretations, such as Metropolitan Ware’s use of Khomyakov, and amplified by ecumenical pressures evidenced by issues with bodies like the WCC), effectively rendering the unique, life-giving Mysteries of the Orthodox Church optional and her definite boundaries negotiable. This is the fruit of ecumenist thinking, which seeks a false unity by diluting the uncompromising truth of Orthodoxy. Fr. Seraphim Rose identified this trend in the “charismatic revival,” describing its orientation as “one of a new and deeper or ‘spiritual’ ecumenism: each Christian ‘renewed’ in his own tradition, but at the same time strangely united (for it is the same experience) with others equally ‘renewed’ in their own traditions, all of which contain various degrees of heresy and impiety!” This critique highlights the danger of prioritizing shared experiences over doctrinal truth, a hallmark of the ambiguity the article condemns.

But true Christian love, as taught by the Saints, is not found in affirming error or offering false comfort. It is found in boldly proclaiming the Truth (Titus 1:13) – the truth that Christ established One Church, His Body, clearly defined by the Creed and defended by the Fathers. We know this Church. We know Her salvific exclusivity. We know the Holy Spirit, in His fullness, dwells within Her, and His work outside is a call to Her, not an endorsement of separation.

Therefore, let us, the faithful, reject these cowardly ambiguities and the deceptions of a watered-down faith. Let us cease to reassure the heterodox in their error, for as St. Paisios warns, we will be judged for giving such false comfort. Instead, let us offer what St. Paisios calls the “good uneasiness” that can lead to salvation – the loving, urgent call to enter the Ark. We must demand clarity from ourselves and others, uphold the unwavering witness of Scripture, the Councils, and the Saints, and “contend earnestly for the faith which was once for all delivered to the saints” (Jude 1:3).

Sources

¹ https://www.jordanville.org/files/Articles/A_Study_of_the_Interplay_of_Piety_and_Theology.pdf